Composition Forum 49, Summer 2022

http://compositionforum.com/issue/49/

Tech Trajectories: A Methodology for Exploring the Tacit Knowledge of Writers Through Tool-Based Interviews

Abstract: Writing researchers have long sought to make tacit writing knowledge explicit, rendering it available for learning and critique. We advance this endeavor by describing our use of the “tool-based interview” (TBI) as a variation of Odell, Goswami, and Herrington’s influential discourse-based interview (DBI). Rather than the product-focused textual disruptions of DBIs, TBIs, by altering authors’ writing tools, disrupt conventionalized writing processes, an approach useful when access to texts is limited for security, privacy, confidentiality, or proprietary reasons. We illustrate this method by describing its use in the development of Journaling, a digital tool for intelligence analysts. After describing our research context and procedures, we describe three sample disruptions from our interviews with intelligence practitioners and the knowledge elicited through these. We conclude with a comparison of the knowledge elicited by our TBIs with that from DBIs and discuss the limitations of each in light of recent work on tacit knowledge.

Introduction

For a variety of reasons such as social equity and pedagogy, compositionists have sought to make knowledge about writing explicit, whether by helping students abstract explicit principles about writing (Adler-Kassner et al.; Yancey et al.), making the role of writing in college settings explicit (Rutz), or making visible the otherwise invisible knowledge necessary for certain genres or modes of writing (Adsanatham et al.; Freedman; Skains). To avoid a hidden curriculum that magnifies privilege and to assist novices with achieving their discursive goals, our discipline has sought to make otherwise tacit writing knowledge explicit and available both to learning and critique (Devitt).

Lee Odell, Dixie Goswami, and Anne Herrington’s discourse-based interview method (DBI) is rightfully a landmark in this endeavor as it has both challenged compositionists to consider tacit writing knowledge with specificity and offered us a concrete method for eliciting it from experienced writers. As this special issue makes clear, this endeavor has continued with variations and adaptations of the original DBI, as well as new methods inspired from it (e.g., Roozen). This endeavor, however, is ongoing as recent work on tacit knowledge and expertise has deepened our understanding of its dynamics—such as the fact that some forms of tacit knowledge may not be explicable at all (Collins)—and as genres and writing practices continue to evolve in tandem with the development of new media and digital writing technologies (e.g., Elliot; Journet et al.; McKee and DeVoss; Miller and Kelly; Pigg et al.; Rice; Slattery; Van Ittersum and Ching).

In this article, we advance this endeavor by describing our use of tool-based interviews (TBI), a method we developed as a variation of the DBI, putting it in conversation with Odell, Goswami, and Herrington’s work and with developments in writing research and tacit knowledge since 1983. To illustrate and critically assess its methodological affordances, we describe our use of TBIs during design ethnography around the development of Journaling, a digital tool intended to aid intelligence analysts with information discovery and analysis and with report writing. Design research and ethnography have long been combined for the design of new tools, products, and documents (Salvador et al.) in ways reminiscent of context-sensitive usability research (Dilger; Mirel), but have also been combined for social research out of recognition that “the design task itself can be used as a vehicle to better understand the everyday lives of the people” (Baskerville and Myers 27). In our case, our team participated in the design trajectory for Journaling much in the way researchers have studied text trajectories (Maybin); through this participation, we sought both to contribute to the design process for Journaling and to develop broader research insights on the social worlds of intelligence analysts, including their writing lives. TBIs, in which interviewees were presented with Journaling prototypes as alternatives to their conventionalized analytic and writing processes, proved useful for both. Rather than the product-focused textual disruption of the DBI, our TBIs, by altering authors’ writing tools, disrupted conventionalized writing processes, prompting analysts to explain writing practices and meanings that may otherwise have remained untold. Like the DBI, however, our tool-based method used disruption to render the familiar unfamiliar for participants and to prompt them to explain taken-for-granted conventions.

In this article, we first describe our research and methodological contexts and procedures for our research on the Journaling project, before illustrating three sample disruptions and the tacit writing knowledge explicated through these using excerpts from our tool-based interviews with intelligence practitioners: (1) disruptions to the documentation of evidence and intertextual relationships; (2) disruptions to typified genre actions and genre relationships; and (3) disruptions to author-reader relationships and authorial control over visibility and circulation. Together, these demonstrate that disruptions to writing processes and tool use can yield tacit knowledge about writers’ socio-rhetorical worlds in ways similar and complementary to the knowledge elicited by DBIs. In the years since Odell, Goswami, and Herrington published their article, the development of new writing technologies has become a more regular occurrence, with the design process of these tools often tapping multidisciplinary teams through practices like design ethnography. We argue that these teams present writing researchers with opportunities both to share composition research insights for the development of more effective writing technologies and to develop new research insights about how writers compose in a range of settings. The TBI is also particularly useful for understanding tacit knowledge about writing in settings that limit researchers’ access to the texts themselves, due to factors such as intellectual property, national security, or privacy. While the case we draw on focuses on writing in a specialized setting, we ultimately argue that TBIs, operating through processual disruption in a way similar to the DBI’s textual disruption, can usefully yield insights on composing across a range of settings where new digital tools may figure, including composition classrooms, and that TBIs offer writing researchers with one more valuable method for understanding the often-invisible knowledge writers draw on as they write.

Research Context and Positionality

In addition to offering a method we believe is useful for writing research, part of the contribution we hope to make here is to raise writing scholars’ awareness that digital technology development projects that are not framed as such can turn out to be relevant to writing research and can benefit from (and benefit) writing-related expertise. In that spirit, we first share the story of how two writing researchers—Gwendolynne and Chris—came to find themselves interviewing intelligence agents alongside a Science and Technology Studies (STS) researcher—Kathleen—and the digital tool that brought them together.

The research we draw on is part of work conducted together at the Laboratory for Analytic Sciences (LAS) at North Carolina State University (NC State)—an R1 public doctoral land-grant university—in the summer of 2016. After the failures of 9/11, the United States intelligence community increasingly sought to collaborate with experts outside intelligence to “explore ideas and alternative perspectives, gain new insights, generate new knowledge, or obtain new information” (Office of the Director of National Intelligence, Directive 205). As part of this initiative, the National Security Agency (NSA) responded by establishing a five-year partnership with NC State in 2013, creating the LAS on the University campus. The goal of this partnership was to foster collaboration between academia, industry, and the NSA to help address emerging problems in intelligence collection and analysis related to big data (National Security Agency). At the time we began working with LAS, approximately fifty analysts had relocated to the lab from other posts at the NSA and other intelligence agencies to collaborate with academic and industry partners on projects related to big data. The project the three of us collaborated on was called the Journaling Application (Journaling).

In summer 2016, Kathleen was a faculty member at NC State and directed its STS program. Having conducted research on the intelligence community for many years using methods like ethnography and participant observation, Kathleen had extensive relationships with local members of the intelligence community, including several grants with LAS to study collaboration and behavioral modeling. The previous academic year, she had hired Chris as a graduate research assistant to work on classroom-based testing of Journaling (Kampe et al.) and enlisted Gwendolynne as a second graduate assistant that spring to complete the classroom phase of the research and begin the phase we describe here, which focused on tool-based interviews with intelligence practitioners in their workplace. At the time, both Chris and Gwendolynne were doctoral students in NC State’s Communication, Rhetoric, and Digital Media program, with research interests and teaching experience in composition and backgrounds in rhetorical genre studies, activity theory, and qualitative research. Gwendolynne had encountered the DBI as part of a directed reading on multimodal composing with Chris Anson.

The Journaling project had its roots in a larger LAS program aimed at reducing the cognitive burden facing intelligence analysts in a big data environment, specifically as they researched and made sense of exponentially larger numbers of sources and datasets and collaborated with increasing numbers of colleagues and stakeholders across agencies and settings. As an initial attempt to understand how analysts were navigating this, LAS had begun with an exploratory program of instrumentation, meaning software tools that logged user activities on their work laptops to capture their processes. This program initially consisted of prototyping software that allowed users to tag media that they were reviewing or producing as connected to a given project and activity (see Dhami and Careless for a list of these activities). In the early prototype stages, this software only possessed the capacity to provide summary reports, such as of the time spent on projects and the resources associated with them. The end goal was to eventually develop a “smart” recommendation system that could productively summarize analysts’ work processes and provide useful insights and recommendations on next steps such as experts, colleagues, datasets, technologies, or methodologies to consult.

While socializing the software, the developers ran into a problem that was fairly predictable when looked at through the lens of Harry Collins’s work on tacit knowledge and expertise. The resulting analysis of their instrumentation data was not particularly useful, not only because it disrupted workflows, causing participants to disable the software, but also because it did not adequately capture analysts’ contexts—the goals and activities the analysts understood themselves to be engaged in and the social meanings and assessments they were using to make decisions. In Collins’s terms (which we’ll elaborate on below), the project understood the analysts’ actions as mimeomorphic, meaning that they “can be reproduced (or mimicked) merely by observing and repeating the externally visible behaviors associated with [the] action, even if that action is not understood” (55-56), when they were more likely polimorphic, meaning that, “the same action may be executed with many different behaviors, according to social context and, again, according to social context the same behavior may represent different actions,” the implication being that these “cannot be mimicked unless the point of the action and the social context of the action is understood” (56). In Collins’s view, polimorphic actions can only be learned and understood through socialization and immersion (56).

The Journaling project was established in 2015 to help address this problem, receiving its name from the ad-hoc analytical journaling some intelligence analysts used to document their analyses. Much as qualitative researchers use analytical memos, analysts use informal journals to document analytical goals, leads, methods, sources, insights, intuitions, etc. to assist them in retracing their own steps and writing formal reports. But Journaling was not designed to operate in a vacuum. Rather, the realized product was to exist within a constellation of interfaces that would not only passively log analysts’ digital activities (as in the instrumentation described above), but also allow and encourage analysts to log activities and analytical insights themselves, and, most importantly, to attach meanings to the resulting records, such as the projects and goals they were attached to and any analytic notes that might be useful.

Developing such a tool was a complex task that would require iterative, collaborative, and ultimately integrative work over months and years. It is at this point that Kathleen became involved with Journaling, a collaboration that was meant to be mutually beneficial as a research opportunity that could yield both social insights that could contribute to the tool’s development and more generalizable insights that could contribute to Kathleen’s research program on intelligence analysts’ work. This approach fit the tradition of design ethnography, which combines design research with social ethnographic research out of recognition that “the design task itself can be used as a vehicle to better understand the everyday lives of the people” (Baskerville and Myers 27), as well as Kathleen’s interventionist research goals that aim for STS-based interventions in “intelligence analysts’ training and how they conduct their work” (Vogel and Dennis 837).

This background explains how the three of us found ourselves interviewing intelligence analysts in the unclassified portion of the LAS workplace reserved for academic and industry collaboration on NC State’s Centennial campus. While we describe our tool-based interview procedures at greater length below, in keeping with anti-racist writing practices, we describe our positionality and participants here. Our participants, in fact, were more racially diverse than the three of us, who are all three White academics, though our team included ethnic and linguistic diversity with one of us a White Hispanic who grew up in a Spanish-speaking home and another a French-American who grew up in a bilingual home. The interviews we draw on in this article were with twelve intelligence practitioners over a two-week period. Because the number of intelligence practitioners working with this and similar LAS projects is extremely small and our interviews elicited participants’ personal experiences and opinions on their workplace, our informed consent promised de-identification, including the use of pseudonyms. Generally, members of the intelligence community are guarded about communicating the details of their workplace and identities to maintain security. We have therefore been careful to remove details that might allow readers to infer their identities. As an aggregate, however, our participants included more women than men, and included White, Latinx, and Black practitioners. Our participants also varied in their ages and levels of experience working in intelligence, which ranged from ten to forty years. All participants had prior experience as intelligence analysts, though half were now working in other roles, such as management. Collectively, our participants had expertise in a wide range of areas including threats, issues, networks, and languages, with training and educational backgrounds in empirical science, education, management, and intelligence processing/editing. Because of the special conditions required to maintain security while allowing us to conduct ethnographic research, our study was approved by both the IRBs of NC State and the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) and our manuscript has been reviewed by a member of DOD for possible security implications.

From Discourse-Based Interview (DBI) to Tool-Based Interview (TBI)

In the section that follows, we describe the methodological and theoretical framework that led us to develop the tool-based interview (TBI) as an adaptation of the discourse-based interview (DBI), sharing the details of how we deployed this approach in our interviews with intelligence analysts about Journaling. The notion of disruption of writing knowledge was key to this adaptation, along with an expanded recognition of writing as material and technological (e.g., Haas). Theoretical developments in rhetoric, composition, and writing studies since Odell, Goswami, and Herrington published their article, especially rhetorical genre theory and activity theory, also figured prominently in the thinking behind our TBIs. Because of our backgrounds in writing studies, from the outset of our work on Journaling, Gwendolynne and Chris were drawn to better understanding the analysts’ writing worlds, such as their genre system, but were challenged both by the role of secrecy in the intelligence community, which restricted our access to the texts produced by analysts, as well as the tacit nature of much writing knowledge. The TBI proved to be a useful method for addressing these twin problems and we believe could be useful to researchers studying writing in a range of contexts, either in conjunction with other methods like discourse-based interviews, or alone when access to texts are limited.

Methodological and Theoretical Background

Odell, Goswami, and Herrington put forth the discourse-based interview partly in response to chemist and philosopher Michael Polanyi’s theory that much of human knowledge is tacit, encapsulated in his observation that “we can know more than we can tell” (4). Polanyi theorized a process of internalization of “proximal” knowledge and tools, such as the details of a face or a moral teaching or a scientific theory, that allows that knowledge to operate tacitly, enabling us to attend to “distal” phenomena, such as recognizing a person, choosing a moral action in a situation, or developing a scientific hypothesis (10). As a scientist himself, Polanyi was interested in the fact that research starts with identifying a problem, but that this needs to be a “good” problem, meaning scientifically original, significant, and, interesting, qualities that have high stakes for researchers’ careers. Polanyi theorized that recognition of a “good” research problem was based in part on “tacit foreknowledge of yet undiscovered things”—what feels like a hunch or intuition is based on internalized tacit knowledge that a researcher may not be able to articulate (23). For compositionists, Polanyi provides another lens for considering arguments such as Janet Emig’s that writing is not best taught “atomistically,” meaning from parts to wholes, such as first from words, then sentences, then paragraphs. Polanyi theorized that higher order distal operations, such as essays, had their own dynamics, independent of the dynamics or rules of the lower order proximal tacit knowledge they rested on, such as sentences (36). Understanding the rules and dynamics of sentence construction, according to this theory, does not fully encompass the knowledge necessary to effectively write a longer work, which has its own set of governing dynamics to attend to, though it might let us attend to those dynamics more economically.

For Odell, Goswami, and Herrington, Polanyi’s insight that higher order decision-making like context-sensitive, rhetorical decisions are grounded in tacit knowledge that writers may not be able to articulate, provided an important exigence for developing the DBI as a method for eliciting some of that tacit writing knowledge from experienced writers. The DBI is designed to elicit this tacit writing knowledge about the writer’s “world knowledge and expectations” (228) through disruption: by substituting alternative textual choices in a writer’s finished text, the researcher disrupts the writer’s sense of the text and of the routinized, tacit choices they made in developing the text, rendering the familiar strange and available for inspection. Because the researcher draws on alternatives from the writer’s own repertoire, the resulting text could have been written by the writer, but lacks rhetorical fit for the situation (e.g., the salutation is not quite right). This works in two ways: first, by drawing the writer’s attention to previously unnoticed and perhaps unconscious writing choices and conventions; second, by prompting the writer, in context of the DBI, to socialize a seemingly inexperienced stranger to the nuances of their rhetorical world, such as gender and power dynamics in the workplace (230-231). Odell, Goswami, and Herrington explain that asking writers to consider alternatives could “create a cognitive dissonance that would enable [the] writer to become conscious of the tacit knowledge that justified the use of a particular alternative” (229, emphasis added). While our summary of the original DBI seeks to represent its approach and goals faithfully, it is important to note that recent work on tacit knowledge, especially Harry Collins’s work, calls into question whether DBIs truly elicit tacit knowledge or whether they elicit some other form of knowledge, something our account below seeks to help address for writing researchers. Collins, for example, draws a distinction between knowledge that remains unspoken due to the nature of relationships (e.g., an author deems that a coworker doesn’t need the information due to some reason like secrecy, privacy, or tact) versus tacit “collective” knowledge that we use to adapt flexibly and effortlessly to ongoing, dynamic social situations. In Collins’s estimation, much of this latter form of tacit knowledge cannot be made explicit by any means, an important caveat as we re-evaluate the DBI’s contribution to writing research in more precise terms.

Writing in 1983, Odell, Goswami, and Herrington’s DBI appeared at the very beginnings of what we have come to call the social turn in composition, a turn that included not only greater attention to writing as a social act but that also included writing researchers integrating social theories that further eroded Cartesian dualities like the mind-society split and that led to more complex understandings of the relationships between individual writers and social contexts. Just a decade later, Carol Berkenkotter and Thomas Huckin, for example, listed some of these influences on their own writing research, including rhetorical genre theory, typification, structuration, habitus, dialogism, activity theory, and social cognition (3). For many in composition, these theories are now familiar frameworks underpinning how we conceptualize and research writing.

For Gwendolynne and Chris, understanding the DBI and the disciplinary exigence to make tacit writing knowledge explicit could not be disentangled from this theoretical legacy and especially from genre theory and activity theory. Within this framework, as Carolyn Miller influentially put it, genres operate as “typified rhetorical actions based in recurrent situations,” forming “an aspect of cultural rationality” (159, 165). As “a frequently traveled path or way of getting symbolic action done,” a genre “embod[ies] the unexamined or tacit way of performing some social action” in a community (Schryer, Records as Genre 207, 209). Berkenkotter and Huckin frame genre knowledge as “a form of situated cognition” or social cognition that is embedded in activity and that is generally acquired through immersion, enculturation, and apprenticeship (3, 13).

For contemporary writing researchers, Odell, Goswami, and Herrington’s method for examining tacit writing knowledge cannot be disentangled from the understanding that writing knowledge entails genre knowledge, including tacit cultural knowledge. Genre’s coupling with category theory, such as in John Swales’s work, has further afforded an understanding of how these cultural categories figure in how writers think and how disruptions help us access that thinking. Cognitive psychologist George Lakoff, for instance, points out that categories are central to “how we think and how we function,” with most of our categorization “automatic and unconscious” and coming to our awareness “only in problematic cases” (6). Building on Odell, Goswami, and Herrington’s focus on understanding the tacit “world knowledge” that figured in writers’ choices, the social view of genre that rhetorical genre theory has reinforced provides additional impetus for prioritizing situational dynamics over a strict focus on form in writing research, particularly exigence (Miller) and communicative purpose (Swales)—the recurring social needs, motives, and stakes of genres from the perspective of those who use them.

Equally salient for our work, genre theory has a tradition of examining moments of disruption, conflict, contradiction, and dissonance in genre use and genre learning as a means to understanding stability, change, and ideology, a tradition within which the DBI’s disruptions fit well. Anthony Paré, for example, examined the ideology sedimented in Canadian social work genres, an ideology rendered visible to him by the disruptions his Inuit students experienced as they struggled with (and resisted) the White “professional” subject position necessary to successfully adopt social work genres. In a study of medical case presentations, Catherine Schryer and her coauthors similarly identified contradictions medical students experienced between the genre systems of school and medicine as they learned the genre, also examining the role of interruptions—a form of disruption—in their learning and in medical discourse. Recently, Heather Bastian has formulated a “disruptive research methodology” for studying student writers’ genre knowledge by disrupting their expectations around the genres of the writing classroom and most especially around the habitual relationships between genres, such as the habitual uptakes of genres with other genres.

For Gwendolynne and Chris, the use of activity theory in past studies of writing, often in conjunction with genre theory (e.g., Bazerman and Russell; Berkenkotter and Huckin; Russell; Schryer et al.), also formed an important theoretical background for understanding the DBI and for thinking about our research approach with Journaling. Activity theory, a theory of human behavior and the mind derived from work by Russian psychologists Alexei Leont’ev and Lev Vygotsky, takes purposeful, goal-directed activity as the basic unit of analysis, formulating this as “activity systems” that can account for interactions between individuals, goals, mediating tools, rules, division of labor, and community (including history and culture) as part of the activity. Through activity, individuals are socialized and internalize “the values, practices, and beliefs associated with their social worlds” (Schryer et al. 67), while also influencing those social worlds by modifying the activity and associated tools. The two interact dialogically. In studies of writing, activity theory has, among other things, helped researchers better account for the role of technologies in writing. Tools, which include but are not limited to material tools (cognitive tools count too), are theorized as “reflect[ing] the experience of other people who tried to solve similar problems,” with tool use representing “an accumulation and transmission of social knowledge” (Kaptelinin and Nardi 70). Learning to use a tool is an act of socialization. Modifying tools therefore implies altering the activity and potentially its sociocultural context, a profound insight for those charged with designing new tools and interfaces for communities, including classroom communities.

Similarly salient is activity theory’s conceptualization of learning and the mind, which has been influential for theories of situated cognition and learning. Activity theory challenges common divisions between the brain and its social context, instead theorizing the mind as developed through interaction with its social, material contexts and therefore part of it—culture is physically reflected in our brains. In addition to the socialization that occurs while participating in activities and learning to use tools, activity theory also conceptualizes how some parts of activities become unconscious and potentially tacit. Within the theory, activity is structured hierarchically, with the larger goal-oriented activity comprised of smaller conscious actions, themselves comprised of unconscious operations that are often “the automatization of actions, which become routinized and unconscious with practice” (Kaptelinin and Nardi 68). Parts of activities therefore become transparent—invisible to the individual—allowing individuals to focus on higher-order goals and actions. Disrupting a formerly transparent operation can render it visible to the individual, turning what was an operation back into a conscious action. Experienced drivers who visit countries where cars drive on the opposite side of the road and place the driver on the opposite side of the vehicle, for example, will have to attend to many operations, like shifting gears with a different hand, that were formerly transparent to them. An update to a familiar digital interface can have a similar effect. In addition to these disruptions, activity theory is often also used to identify contradictions both within and between activity systems, with contradiction theorized as a key driver of change (e.g., see Schryer et al. 69, 71).

The theories we outline above, specifically the insights they provide about the many dimensions of writing knowledge that may operate tacitly, together provide an additional rationale for DBIs as a method for researching writing. In addition, however, they also provide insight into how a wider range of writing-related disruptions may provide insight into tacit writing knowledge, such as disruptions to writing tools, genre categories, or genre relationships. Our Journaling interviews focused on the disruptions created by a new writing tool, a disruption that seemingly would only generate process-related tacit writing knowledge. We found, however, that tool-based disruptions, at least in the case of tools that also mediate the relationships between texts and people, can also elicit tacit socio-rhetorical knowledge similar to that elicited by DBIs.

Before delving into the specific procedures we employed, however, it is important to address more recent work on tacit knowledge, specifically Harry Collins’s influential contributions to that topic in science studies over the last several decades. His 2010 book Tacit & Explicit Knowledge synthesizes much of that work, providing a valuable vocabulary we have found useful for deepening our own thinking on the subject. Aiming for greater specificity, Collins identifies the many ways knowledge may be tacit, or not explained, developing three larger categories of tacit knowledge. Relational tacit knowledge (RTK) is “weak” tacit knowledge, meaning that it could be explained but has not been due to some contingency around how our social lives are set up, such as expectations of secrecy or lack of awareness that an individual does not know something. Collins argues that many efforts at making tacit knowledge explicit are centered on RTK, such as Odell et al’s interviewee’s explanations about their relationship with the recipient of their letter, information the interviewers would not normally have access to due to their relationships to both parties. Somatic tacit knowledge (STK) is “medium” tacit knowledge, meaning that it is more difficult to explain as it resides in the body, such as our knowledge of how to balance on a bicycle or how to touch type. Collective tacit knowledge (CTK) is “strong” tacit knowledge, meaning that it may not be explicable at all. Collins argues that humans are by nature “social parasites” uniquely able to absorb social knowledge that exists at the level of the collective, not the individual brain—we “feast on the cultural blood of the collectivity” (131). Due to our nature, we engage in “polimorphic actions,” meaning that “the same action may be executed with many different behaviors, according to social context and, again, according to social context the same behavior may represent different actions” (56). These cannot be mimicked, and so are in direct contrast with “mimeographic” actions, which can be mimicked; according to Collins, polimorphic actions can only be learned through socialization (56). This explains why, in one instance, a text that resembles a research article may be correctly interpreted as intervening in a research conversation, and in another, may be equally correctly interpreted as a parody, though it mimics the same form (see Swales for an example). As social animals, we are sensitive to more dimensions of social knowledge than we can explain, bringing these to bear on our social judgements and polimorphic actions in real time, often without our awareness. For artificial intelligence researchers who may be tempted to try, Collins quantifies the futility of attempting to explicate all of the CTK necessary to build an English-language machine that could meaningfully ask and answer 100-character questions and answers in the way humans can understand them (128). His answer is sobering and provides perspective on any attempt to explicate tacit knowledge. A large part of the tacit knowledge explicated by either DBIs or TBIs is likely to be “weak” relational knowledge, with only a small part comprised of “strong” collective knowledge. And even if our methods do help explicate collective knowledge, they will logistically be unable to explicate it completely. While Collins’s work is grounds for humility in our research and teaching, writing scholars’ attunement to the situational nature of all rhetorical interactions positions us well to be attentive to the partiality of any attempt to document, explain, or systematize the knowledge individuals bring to these interactions.

Procedures for our Tool-Based Interviews

As described above, the one to two hour interviews we draw on to illustrate our tool-based interview method took place with twelve intelligence practitioners over a two-week period during the summer of 2016. Prior to our interviews, participants attended a presentation on the most recent version of the Journaling prototype given by the development team, which we also attended. As part of the presentation, the developers demonstrated Journaling and explained its functionality within the context of their analytic work—how analysts would interact with it, what it would record, what it would provide them, how they might use it. The developer also described anticipated next steps for Journaling’s development, such as its potential use to recommend analytic steps and resources for analysts or help them identify biases in their analyses. Finally, attendees had the opportunity to ask questions of the developer at the end of the presentation, a period which resulted in a larger conversation among attendees about their work and needs. In addition to this presentation, some analysts had tested the prototype or earlier versions of it. While it would have been ideal for all interviewees to have tested Journaling in the context of their work, the demonstration provided participants with a concrete, visual, and interactive demonstration that allowed them to imagine how it could fit in (or disrupt) their analytic processes.

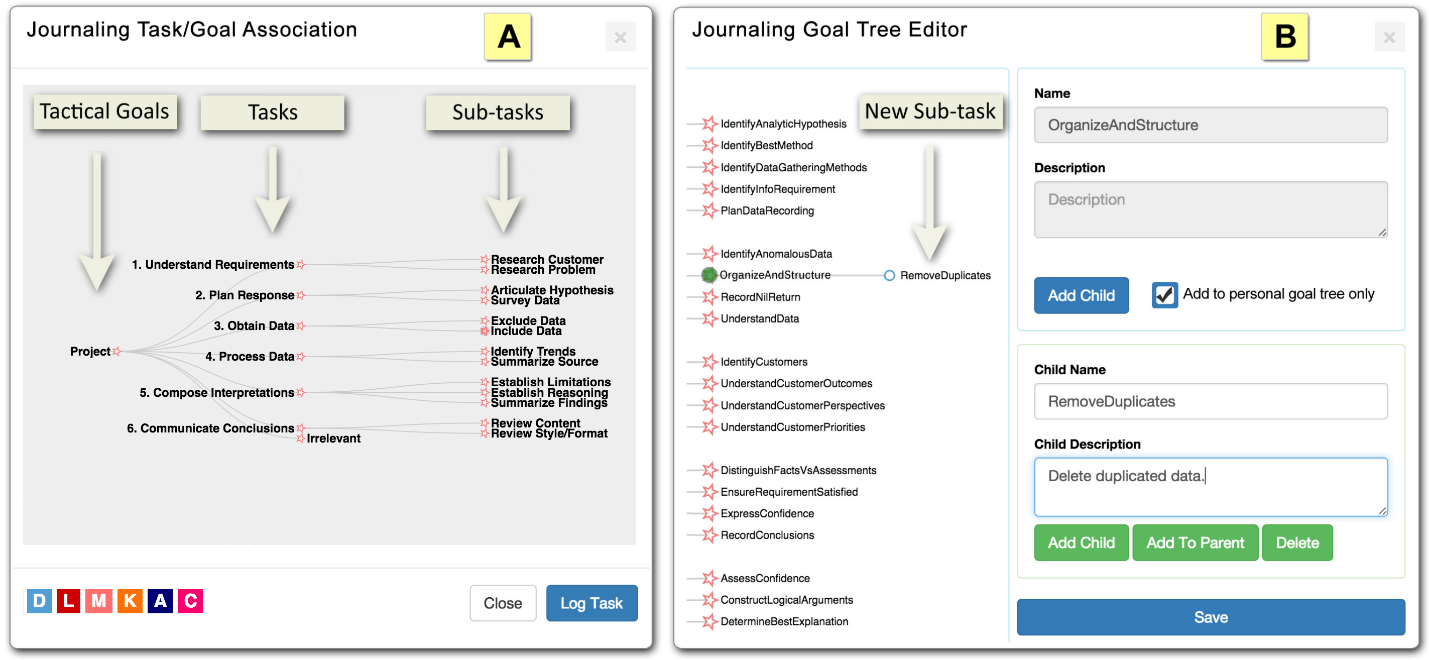

During the presentation, for example, analysts learned that Journaling would passively record their actions, such as the databases, documents, and other resources they accessed, and associate these with specific projects and tasks that they could then return to easily. While some of the associations would occur automatically, analysts would also be able to edit how their actions and resources were categorized using an interactive “goal tree editor” (Figure 1). Users would also have the opportunity to include analytic notes (hence the name Journaling). During the Q&A, attendees noted their excitement at seeing how easily the developer was able to return to a PDF he had previously accessed, discussing the topic of PDF/document annotation at some length. Because many projects are collaborative, the developers also demonstrated how Journaling projects could be associated with teams as a means to share resources, analytic insights, and writing, such as project-related notes, with fellow analysts as well as with managers. To illustrate a wider range of uses similar to how paper-based work journals or logs might serve multiple purposes, the developers illustrated how Journaling could later generate activity reports and even analyses of activity to help analysts reflect on and refine their processes as well as to assist them in writing their annual performance reports.

Figure 1. Screenshot of Journaling’s goal tree editor from the prototype demonstration.

Because the demonstration took place a few days before our interviews and a few participants were unable to attend, the beginning of each interview included a detailed description of Journaling’s functionality similar to the description above. In addition to this description, the interview included background questions on interviewees’ work experiences, tool-based questions on Journaling and participants’ research and writing processes, and general questions on their attitudes toward collaboration and privacy, since Journaling had implications for both of these. Much as DBI questions ask writers to entertain hypothetical rhetorical scenarios through hypothetical writing choices, our tool-based interview questions asked participants to entertain Journaling as a hypothetical part of their research and writing processes, speculating about how this might be generative or disruptive to those processes. For example, in considering how Journaling might prompt analysts to categorize the actions it recorded or, later, provide recommendations for other actions or resources, we asked analysts to consider whether and when they would accept those sorts of interruptions to their processes:

Generally speaking, when would you allow the application to bother you or not bother you? Think in terms of time of day, or relative to other activities.

As interviewees considered hypothetical collaborative analytic and writing scenarios mediated by Journaling, we asked them whether the new visibility and access it would provide into colleagues’ processes, resources, and writing would be productive and acceptable:

If you were working on a team, would you find it productive to be able to see [through Journaling] what your colleagues were working on within that project (i.e., resources viewed, material produced, etc.)? In essence, would you find it useful to see their Journaling data? Why? As a corollary, would you be comfortable with them being able to view your Journaling data? Why or why not?

Because our interviews were intended to simultaneously help us research this social world and assist the developers of the tool, some of our questions also asked interviewees to conjecture about possible new or revised functionalities they thought could be useful to their work. For example, we asked whether they could think of additional features that might assist them in remembering, organizing, or reporting on their analytic processes:

Think about the work you do and difficulties you have encountered with regards to recalling/organizing information or reporting the work you’ve done. Are there any additional features that we could add to the Journaling application that would help you in those tasks?

While these questions were not directly framed as about writing, but rather about the analytic process holistically, the disruptions and alternative processes they asked participants to entertain produced rich insight into both their processes and products and, more importantly, their socio-rhetorical worlds, such as their genres, genre relationships, and author-reader relationships.

Disruption 1: Documenting Evidence and Intertextual Relationships

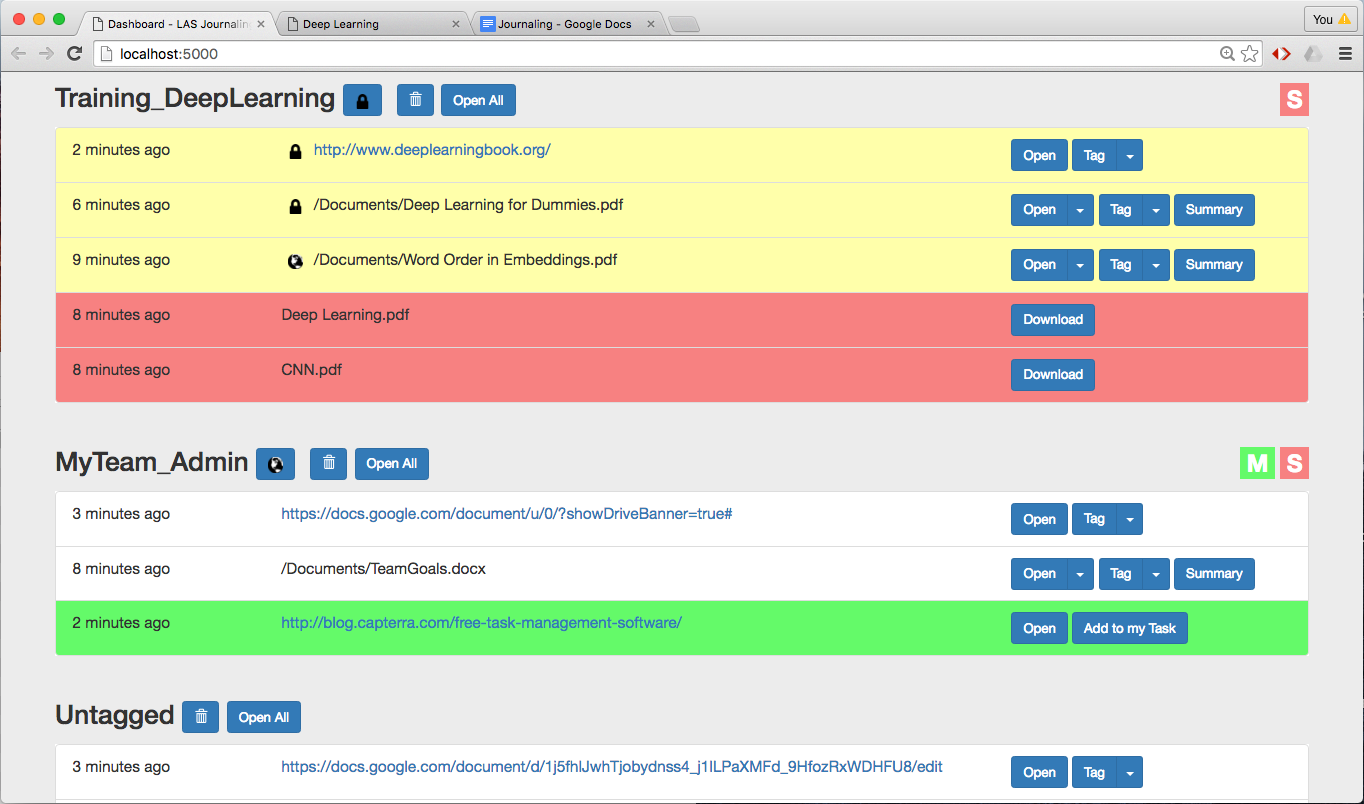

The three sections that follow each describes a moment illustrative of the types of writing-related knowledge made explicit by our TBIs and specifically by the disruptions these provoked. The first of these came towards the end of a combined interview with Debi and Jim and focused on citation of sources. (As noted above, all participant names are pseudonyms.) At the earlier presentation, Debi and Jim had seen the Journaling dashboard, which showed how the tool would create records of activity using URLs and filenames as well as how users could tag records to associate them with specific projects and goals (Figure 2). During the interview, Gwendolynne had recalled this presentation and elaborated on it with oral description of Journaling’s features, such as its anticipated ability to “keep track of all the resources associated with a given project, facilitating rapid access.”

Figure 2. Prototype of Journaling dashboard as shown to interviewees.

While the conversation had thus far focused on issues around usability and collaboration, Debi’s interest had been piqued by a moment during the presentation when the developer had shown the dialog box for users to tag records with their own goals and descriptions. The development team had been most focused on describing how the record of analysts’ time spent with sources, in conjunction with records of the projects and goals they were being used for, could be used to create visualizations and activity reports that could help analysts reflect on their analytical processes, perhaps identifying best practices as well as inefficiencies or cognitive biases. But while Debi was interested in these possible uses, the visual represented a disruption of her usual process. Rather than as a prompt for reflection, her typical need to track sources corresponded to community exigences around documenting the evidence and warrants for claims and recommendations (see Office of the Director of National Intelligence, Directive 203), including contextual information about sources.

After a general question about additional features either Debi or Jim could think of that might be useful, Debi turned the conversation to citation:

Debi: So, with the, I’m thinking way down in the weeds, which is kind of how that works with us . . . with the goal pop-up window—that has the abstract on there, right? So, if it had, to me, personally, as a researcher, if it also had the citation on there (laughing), to me, that would be very cool.

Gwendolynne: Yeah?

Debi: (teasing) In APA style (laughs).

G: (writing it down) I’ll mention that: APA citation.

D: (apologetically) No, I mean, they don’t have to do that . . . because they have converters for that.

G: Uh-huh, yeah. That’s what I use Zotero for. It’s great.

D: But, you know, if we’re asking them.

G: Yeah, that seems more, um, meaningful than just a URL.

Debi was reacting here to seeing that URLs would be the primary bibliographic information stored and displayed by Journaling. While not framed as a conversation about writing and citation, based on her prior knowledge and typical writing process, the sample record struck Debi as incongruent with her typical needs. Drawing Jim in the conversation, Debi sought to tie her personal knowledge with that of the collective community:

D: Right, and I don’t know exactly how things are, you know, sources are being identified at this point in the community. (to Jim) Do you? (to G) But to have, you know, where to find it as well as what it is. If that’s a central document to what you’re doing. That’s important.

Jim: So, it’ll say source, then it’ll be the document identification number, where it is in the database, and then there’s just a brief [inaudible] of what it is.

D: So, is it like that in the DA database too?

J: It’s similar. It’s more like the Chicago style than it is the APA Style, but, yes, it’s similar.

D: But citation, nonetheless.

Without the interviewer prompting it, we see in this exchange how a process-related disruption—specifically seeing information the writer would normally collect for one purpose being collected for another—elicited writing knowledge. Not only did Debi express a need for bibliographic information about her sources, information that serves as important social cues for fellow researchers, analysts, leadership, policy officials, or informed readers who might read her reports, but she also named a specific citation style associated with a social scientific frame, providing clues about the type of research she conducts and the epistemological orientation of that research. The teasing exchange between Debi and Jim over APA versus Chicago style, an exchange with overtones of a longstanding, light-hearted disagreement, suggests a pluralistic genre system within which actors with differing epistemological backgrounds come together to try to reconcile these differences in the interest of a common goal. Jim’s preference for Chicago style points towards qualitative research expertise in the historical, anthropological, or sociological traditions rather than experimental methods.

Both, however, expressed a value on documenting sources in a manner that would provide readers with more “heuristic cues” for evaluating the credibility of sources and claims built on those sources (Priest). Eliciting this value and the academic writing conventions Debi and Jim draw on in their intelligence reporting tells the researcher much about the genre resources being repurposed in this community’s writing and the fact that conventions and values around attribution may be more familiar to writing researchers than might be anticipated, at least in some genres in the intelligence genre system. The rhetorical orientation of this writing convention—communicating socially-meaningful information about the provenance of sources for readers, not simply a current digital location—also points to how this disruption may have been inadvertently created by the tool developers, whose engineering frame reflected a practical focus on locating and storing information to solve organizational and cognitive problems rather than on communicating socio-rhetorical meanings around how and by whom that information was produced through bibliographic conventions developed precisely to communicate the intertextual relationships around texts. This brief exchange over one small moment of disruption illustrates how the TBI not only yielded design-focused research insights that could help the development team design a better tool more suited for the values and traditions of its social context, but also yielded writing knowledge around intertextuality and attribution that Debi and Jim might not otherwise have thought to share.

Disruption 2: Remediating Genres and Revising Genre Relationships

While our first disruption highlights the view of intertextual relationships between reports and their sources made visible by our TBIs, our second disruption illustrates our TBI’s special affordance for making the relationships between genres in the intelligence genre system visible. Journaling, in fact, by remediating and “instrumenting” the ad-hoc, occluded genre of the analytic journal, changed the possible roles it could play in the intelligence genre system, also potentially changing the relationships between other genres in the system. For our interviewees, the potential deviation from the business-as-usual relationships between genres functioned as another disruption that elicited more genre knowledge. Like academic disciplines (Toulmin), intelligence workplaces include a combination of epistemic genres and professional genres, one set mediating intelligence knowledge production and the other mediating intelligence workplaces and professional relationships. While Journaling was primarily conceived to intervene in the epistemic work of intelligence analysts (e.g., analyzing big data), the tool was quickly also seen as a way to intervene in recurrent professional problems and genres, such as the problem of training new analysts and evaluating performance. In the same interview we drew from earlier, for example, Jim and Debi considered the affordances of a digitized, “instrumented” journal of analytic activity and how this might be taken up in the performance review genre and in training-related genres:

Jim: Well, certainly, if you could feed it to your performance review... You know, I’ve seen some analysts here who have done work that’s gotten public recognition and some kind of director’s award. Oscar has stuff.

Debi: That would be like a finished—

J: Yeah, but I mean if you could catch, if you could see how he got to that.

D: Oh, that would be neat—

J: That could be a story. A story he could tell in his performance review. It’s a story he could tell in a classroom. It’s a story. I mean...

D: Well, right, and that would be an interesting way to gather best practices and use those in training environments for those classes.

J: Yup. So, imagine when the people who hit it out of the park... You want to capture that. It’s like batting practice, right? You want to get the right movement and swing and... But you have to model somebody who does it well, yeah.

Here, Jim reflects on the connection of epistemic intelligence genres (analytic reports) with professional genres (performance reviews, training materials) as well as public epideictic genres (awards). As he reflects on how Journaling disrupts the usual function of an analytic journal, he sees possible new functions and genre relationships that illuminate the role and importance of professional genres in the intelligence workplace. Rewarding quality intelligence analysis is clearly an important social action in this community. And, interestingly, he and Debi also identify another problem for the community similar to the one we explore in this article: how to make visible the knowledge and practices that go into exceptional intelligence analysis in order to impart them to novice members of the community of practice.

Other interviewees, like Joan, an interviewee with managerial experience, expressed similar reflections, reinforcing that these twin problems functioned as recurring exigences within the community:

Gwendolynne: And so, could it be helpful with the writing piece too, you think?

Joan: Yeah, that would definitely be helpful with the writing piece. And, you know, not just for the analyst, but us. Again, that’s something I think will help the managers kind of understand exactly what the analyst had to do to achieve like an objective or a goal.

Right now, we’re in the process of writing these performance evaluations. So, on our team, we have a couple of junior people and they are phenomenal. And I think they often fail to realize the work, the intensity of the work that they’ve been doing. So, I have to kind of go back and say, you really need to... make the managers understand exactly what was involved. You didn’t just do this, you know. They’ll tend to say, well, you know, I just developed it.

I mean, you went through a whole series of tasks and stacks and testing and evaluation and you really need to kind of detail... managers really don’t understand the level of work, how labor intensive it is, how to think about what type of resources you might need for the next year based off of all the work that was already done, or that wasn’t done that you might want to have done something, I don’t know, differently.

Here, Joan conjectures about how the Journaling tool might rework genre relationships. Additionally, reflecting on this possible disruption to typified relationships prompts her to articulate the multiple communicative purposes that performance review interactions between managers and analysts can accomplish, both for individual analysts (recognition) and for the community’s work towards the larger mission (resources for work that still needs to be accomplished).

In addition to eliciting knowledge about recurring exigences and the typified genre relationships that have developed to respond to them, the potential disruption to those relationships represented by Journaling also provoked interviewees to articulate another important dynamic regulating the relationships between those genres: restrictions on audience tied to classification. Jim and Debi provide a useful example of this, describing the implications of remediation for a community for whom medium sometimes points to audience and sometimes to levels of restriction:

Gwendolynne: Are there instances when you would not be comfortable with having people (such as coworkers) viewing your data?

Jim: Restricted analytic. Anything super compartmented.

G: Super...?

J: Compartmented. So that if they didn’t have the—

Debi: Classification level.

J: If they had a classification that wasn’t—and the classifications here are, uh...

D: Which is a whole other ball of wax that we have to deal with if they want to put that on the high side (classified side), because once you start collaborating, then, you know...

J: So at [intelligence agency] in addition to the classifications here, where there are classifications for individual programs, there are classifications for, they call it the “bigot list.” And it’s how many people have—who and how many people have access to very specific information about sources and methods or about National Security Council objectives or programs undertaken to support presidential directives. And then there’s some stuff that, you know, eventually they’ll narrow it down to a handful of people and, um, that stuff never... In my experience, that stuff is seldom transmitted electronically, it’s usually hand carried in paper form, and so it’s kind of out of that world.

In this interaction, Gwendolynne’s question about the possible disruption Journaling could represent to audience elicited social knowledge about restrictions to audience, such as the “high side” versus “low side” and the “bigot list,” as well as the rhetorical implications medium could carry within this community, functioning indexically to denote the most classified information and restricted audiences. Control over reader access plays an especially important and regulated role in this genre system, something elicited by Journaling’s potential disruption to typified genre relationships and the rhetorical interactions these represent.

Disruption 3: Reworking Author-Reader Relationships and Authorial Control Over Visibility and Circulation

Control over reader access, in fact, merits more extensive treatment as Journaling’s disruptions to visibility and circulation not only elicited knowledge about genre and media relationships, but also about social meanings around authorship and authority and about rhetorical sensibilities around communicating certainty and probability. An interview with Joan illustrates this well as it became apparent to her that not only could Journaling disrupt genre relationships at the level of finalized texts but also at draft stages that could include provisional analyses and assessments. Controlling reader access, then, was not just a matter of clearance to read particular texts or topics, but also a matter of access to earlier stages of those texts and analyses, an issue she explained as intertwined with issues of authority and author accountability. Journaling, by potentially facilitating collaboration on and circulation of informal texts at earlier, more provisional analytic stages, could disrupt authors’ control over their knowledge claims and how or whether they could qualify and hedge them, something normally achieved through highly conventionalized use of linguistic certainty and probability indicators. For Joan, addressing Journaling’s potential disruption to community norms around authority and communication of certainty meant authors would need control over releasability and annotation to provide necessary context about analyses:

Gwendolynne: There are so many different ways the data (used as the basis of your analysis) can be used, right? ... Are there implications, like safeguards, you’d like to see for how it’s looked at and used?

Joan: That’s a good point. (pauses to think) You know, maybe as an analyst if I use a specific dataset, I guess I’m wondering, though, if maybe I would like to have a feature that says, I don’t mind releasing this dataset to a broader audience. Or especially if I have my own comments, or, um, opinions in there. I would like to have the option to say, I don’t care if anybody reads my Journaling comments or my opinions or I would like to maybe say I would like to keep this private for me. Or maybe only within my peer group. I would like to have some options. Especially if you’re still working through the process and nothing’s conclusive yet, you don’t want someone to come in and take a specific dataset out of context. And then use it for something else.

G: So it sounds like annotation would be super important and then, kind of, different levels of annotation?

J: Yeah, I would like to have some kind of releasability feature. You know, like, you can release this at a certain level or I don’t want this released at all because I’m still trying to figure this out.

G: Like a draft.

J: Yeah, like a draft.

G: Yeah, yeah. Um, like a personal note that you know you’re going to change.

J: Exactly, right.

G: Yeah, okay. That makes sense. Any other thoughts you have on that? Thinking about how it might be misused and adding the context, it sounds like annotation would be one of the main things. Are there any other?

J: Well, just a part of that, an extension of the annotation, is I only want it to be maybe used within this context. You know, so a lot of times, say you think about extracting something and I’m tying it to something else. I want to be cautious that, um, it’s not taken out of context. It’s a way that I want to make sure that, um, if something is used, it’s used appropriately. Even if you say I want to release it to a broader community.

In this interaction, it became clear that control over circulation and the ability to contextualize and qualify knowledge claims and evidence are key to writing effectively within this community, so much so that, in context of Journaling’s potential disruption to the conventional ways of addressing those needs, Joan found it necessary to find other ways to address them, such as through annotation. For Joan, the possibility of sharing in-process drafts and analyses violated the typical genre sequence and the amount of author control over release of information embedded in that sequence, revealing tacit knowledge about authorial roles and responsibilities in this genre system. Based on this, it seems analysts-as-authors feel responsible for how their analyses are repurposed (e.g., “and then use it for something else”). In addition, however, Journaling’s potential to “learn” from analysts and eventually make recommendations of certain datasets or analytical processes over others also troubled and disrupted Joan’s sensibilities around authorship and accountability as an analytic recommendation is a form of selection, meaning other possible pieces of evidence or analytic approaches have been discarded and hidden from view:

Joan: So, if I have to go and speak to something, about an event that happened, I’m supposed to be the subject matter expert. Um, and if I’m using a capability or technology to help me step through this process of understanding and coming to this resolution or this outcome, I need to know what was involved. Because you’re going to get asked a lot of questions, right, by a policy maker or somebody at a higher level. How did you come to that conclusion, or, what happened? So, you want to be able to speak to the data that was used.

G: Right, yeah, it cannot be a black box.

J: Right. Exactly.

Here, Joan reveals additional sensibilities around author roles, specifically the fact that intelligence analysts are responsible for their analyses, meaning they are responsible at some level for the consequences of those analyses, such as wars. While in the public imagination, intelligence reports are not “authored” by individuals, existing as “the intelligence,” Joan’s responses to the hypothetical disruptions presented by Journaling indicates that individuals do feel a sense of authorship and responsibility over their reports. Joan cannot afford to have an algorithm doing her thinking for her as, ultimately, she will be held accountable for the resulting analysis and needs to be able to speak in detail about the evidence and reasoning that led her to make specific conclusions in her report. Like Jim and Debi’s discussion on citation, Joan’s interview points to a writing culture that stresses explicit and direct links between claims and evidence as well as explicit descriptions of inferential reasoning and the warrants behind claims and evidence. While this particular TBI does not provide direct textual examples of conventions around this explicit reasoning or around certainty and probability indicators, it does provide rich insight into the socio-rhetorical knowledge and sensibilities tied to those conventions.

Discussion

In the years since Odell, Goswami, and Herrington introduced the discourse-based interview as a means for eliciting tacit writing knowledge, writing researchers, as well as researchers in a range of other fields, have shed light on the complexity of this endeavor. One of the chief challenges for researchers cognizant that “texts only have significance in relation to specific social contexts,” for example, is the challenge of getting textual and contextual data from a social scene “to talk to each other” (Schryer, “Investigating” 33, 46). In addition to the affordances offered by disruptions to tacit writing knowledge, it seems likely that one reason the DBI has been so influential is that it inherently puts the two—text and context—into methodological conversation with each other and does so in partnership with social agents rather than the researcher doing this alone, a posteriori. Our expanded view of writing since the 1980s, however, points to how other writing-focused interactions and disruptions, such as the tools and processes writers use in particular contexts, can also yield rich insight into writing in those social contexts.

The tool-based interview method we describe and illustrate above, we believe, is one additional research strategy writing researchers can usefully employ to understand the tacit knowledge writers often draw on to respond to rhetorical situations. Notably, while disruptions to writing tools and processes seem most likely to yield insight into the processual and perhaps somatic dimensions of writing in those contexts—what Collins calls somatic tacit knowledge (STK)—the three examples we describe above demonstrate that process-related disruptions can also yield socio-rhetorical knowledge, such as about genres and genre relationships, and social roles, such as authorial responsibilities. In Collins’s framework, it seems likely that a fair amount of this socio-rhetorical knowledge is relational (RTK) rather than collective (CTK)—when researching the intelligence community, for example, much of this knowledge remains unexplained because of its culture of secrecy. Collins, however, stresses that collective tacit knowledge is what allows us to make social judgements that enable us to interpret and respond to social context flexibly (120), understanding, for example, the distinction between an authentic utterance and a parody or between a typo and a perposefully misspelled word. Based on this definition, it seems that both DBIs and TBIs do provide some understanding of the usually tacit knowledge that goes into making those social judgments. Jim, for example, explained the social judgments made about media in his particular social context (“it’s usually hand carried in paper form, and so it’s kind of out of that world”), while Joan provided insights into social judgments about when and with whom to share analyses-in-progress. In Odell, Goswami, and Herrington’s sample DBIs, Margaret Smith provided insight into social judgments about when to sign her name in ways that would de-emphasize gender (230-231). Even these examples underscore Collins’s point that there may be so many variations and so many nuanced gradations of social judgment at work to make it logistically unfeasible to render all CTK explicit, but they also suggest that some of the social meanings and values that go into them are explicable.

One limitation of our tool-based interviews is that they do not naturally connect text and context. In our case, our interviews had no direct connections with texts and so our examples could not tie the socio-rhetorical knowledge we learned about to rhetorical or linguistic analysis of sample texts. That said, this knowledge points quite clearly to genre conventions we could follow up on with other methods. The intelligence world, for example, clearly a writing world, publishes writing guides (“meta-genres”) that could be usefully put in conversation with the knowledge explicated by our TBIs (e.g., Office of the Director of National Intelligence, Style Manual and Official Style Bookand Writing Guide; Software Engineering Institute). Odell, Goswami, and Herrington explore the conundrum of how to select features and alternatives to present to participants, acknowledging that there may be others that could yield more information (230). TBIs seem well positioned to help researchers make more informed choices about which analytical leads to follow with other methods, such as, in this case, examining the use of probability and certainty indicators in intelligence reporting. It is also worth pointing out that writing researchers may sometimes, as in our case, wish to study a writing scene where social actors cannot provide direct access to their writing (RTK), such as due to security, privacy, confidentiality, or proprietary reasons. Under the right circumstances, TBIs can, we believe, offer a useful way to learn more about that writing without accessing the texts themselves. The nature of the knowledge explored, of course, will be tied to the affordances of the writing tool in question—in our case, it had the potential to rework many textual and social relationships and so we were able to learn much about those relationships.

While the intelligence community may seem far afield from composition’s typical focus on the first-year composition classroom, writing classrooms are spaces that are often the subject of technological experimentation. Some of the tools and technologies tested in that space may not be ostensibly “writing technologies,” but as our example illustrates, even seemingly writing-adjacent technologies, such as “ICTs” (information and communications technologies), are often writing technologies when writing is looked at holistically and socially. A new learning management system (LMS), for instance, can disrupt classroom genre systems, such as the relationships between student texts and teacher feedback, offering an opportunity both to better understand the exigences, actions, and stakes of those genres for teachers and students and to intervene positively in the development of classroom technologies. Classrooms are also spaces with privacy-related constraints on access to texts, something TBIs can help address. While TBIs depend on a special set of circumstances, such as our collaboration, we believe more of these opportunities may exist for writing researchers than many realize and that this can be one more useful research strategy in the wide repertoire necessary to understand writers and writing in the world.

Acknowledgements: This material is based upon work supported in whole or in part with funding from the Laboratory for Analytic Sciences (LAS). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the LAS and/or any agency or entity of the United States Government. The authors wish to thank Paul Jones, whose design and engineering work made this project possible, as well as Debi, Jim, Joan and the other analysts who so generously participated in these interviews.

Works Cited

Adler-Kassner, Linda, et al. The Value of Troublesome Knowledge: Transfer and Threshold Concepts in Writing and History. Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012, https://compositionforum.com/issue/26/troublesome-knowledge-threshold.php.

Adsanatham, Chanon, et al. Re-Inventing Digital Delivery for Multimodal Composing: A Theory and Heuristic for Composition Pedagogy. Computers and Composition, vol. 30, no. 4, Dec. 2013, pp. 315-331, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2013.10.004.

Baskerville, Richard L., and Michael D. Myers. Design Ethnography in Information Systems. Information Systems Journal, vol. 25, no. 1, 2015, pp. 23-46, https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12055.

Bastian, Heather. Capturing Individual Uptake: Toward a Disruptive Research Methodology. Composition Forum, vol. 31, Spring 2015, https://compositionforum.com/issue/31/individual-uptake.php.

Bazerman, Charles, and David R. Russell. Writing Selves, Writing Societies: Research from Activity Perspectives. WAC Clearinghouse and Mind, Culture, and Activity, 2003.

Berkenkotter, Carol, and Thomas N. Huckin. Genre Knowledge in Disciplinary Communication: Cognition/Culture/Power. Lawrence Erlbaum, 1995.

Collins, Harry. Tacit and Explicit Knowledge. University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Devitt, Amy. Teaching Critical Genre Awareness. Genre in a Changing World, edited by Charles Bazerman et al., Parlor Press and the WAC Clearinghouse, 2009, pp. 337-351.

Dhami, Mandeep K., and Kathryn E. Careless. Ordinal Structure of the Generic Analytic Workflow: A Survey of Intelligence Analysts. IEEE, 2015, pp. 141-144, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpls/abs_all.jsp?arnumber=7379737.

Dilger, Bradley. Extreme Usability and Technical Communication. Critical Power Tools: Technical Communication and Cultural Studies, edited by J. Blake Scott et al., State University of New York Press, 2006.

Elliot, Norbert. Writing in Digital Environments: Everything Old Is New Again. WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 38, no. 1, 2014, pp. 149-172.

Emig, Janet. Non-Magical Thinking: Presenting Writing Developmentally in Schools. Writing: The Nature, Development, and Teaching of Written Communication, edited by Carl H. Frederiksen and Joseph F. Dominic, vol. 2, Erlbaum, 1981, pp. 21-30.

Freedman, Aviva. Show and Tell? The Role of Explicit Teaching in the Learning of New Genres. Research in the Teaching of English, 1993, pp. 222-251.

Haas, Christina. Writing Technology: Studies on the Materiality of Literacy. Routledge, 1996.

Journet, Debra, et al., editors. The New Work of Composing. Utah State UP/Computers and Composition Digital, 2012, https://ccdigitalpress.org/nwc.

Kampe, Christopher, et al. Bringing the National Security Agency into the Classroom: Ethical Reflections on Academia-Intelligence Agency Partnerships. Science and Engineering Ethics, vol. 25, 2019, pp. 869-898, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9938-7.

Kaptelinin, Victor, and Bonnie A. Nardi. Acting with Technology: Activity Theory and Interaction Design. MIT Press, 2006.

Lakoff, George. Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about the Mind. University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Maybin, Janet. Textual Trajectories: Theoretical Roots and Institutional Consequences. Text & Talk, vol. 37, no. 4, 2017, pp. 415-435, https://doi.org/10.1515/text-2017-0011.

McKee, Heidi A., and Dànielle Nicole DeVoss. Digital Writing Research: Technologies, Methodologies, and Ethical Issues. Hampton Press, 2007.

Miller, Carolyn R. Genre as Social Action. Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 70, no. 2, May 1984, pp. 151-167.

Miller, Carolyn R., and Ashley R. Kelly, editors. Emerging Genres in New Media Environments. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Mirel, Barbara. Advancing a Vision of Usability. Reshaping Technical Communication: New Directions & Challenges for the 21st Century, edited by Barbara Mirel and Rachel Spika, Lawrence Erlbaum, 2002, pp. 165-187.

National Security Agency. NSA Creates Partnership With North Carolina State University. National Security Agency/Central Security Service, 15 Aug. 2013, https://www.nsa.gov/Press-Room/Press-Releases-Statements/Press-Release-View/Article/1630949/nsa-creates-partnership-with-north-carolina-state-university/.

Odell, Lee, et al. The Discourse-Based Interview: A Procedure for Exploring the Tacit Knowledge of Writers in Nonacademic Settings. Research on Writing: Principles and Methods, edited by Peter Mosenthal et al., Longman, 1983, pp. 221-236.

Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Intelligence Community Directive 203: Analytic Standards. 2 Jan. 2015, https://fas.org/irp/dni/icd/icd-203.pdf.

---. Intelligence Community Directive 205: Analytic Outreach. 2008, https://irp.fas.org/dni/icd/icd-205.pdf.

---. Official Style Book, 2011 and Writing Guide, 2013. Government Attic, 2014, https://www.governmentattic.org/12docs/ODNIstyleManual_2011_2013.pdf.

---. Style Manual & Writers Guide for Intelligence Publications. 8th ed., Directorate of Intelligence, 2011, https://irp.fas.org/cia/product/style.pdf.

Pigg, Stacey, et al. Ubiquitous Writing, Technologies, and the Social Practice of Literacies of Coordination. Written Communication, vol. 31, no. 1, 2014, https://wcx.sagepub.com/content/early/2013/12/08/0741088313514023.abstract.

Polanyi, Michael. The Tacit Dimension. Revised ed., University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Priest, Susanna. Critical Science Literacy: What Citizens and Journalists Need to Know to Make Sense of Science. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, vol. 33, no. 5-6, 2013, pp. 138-145.

Rice, Jenny Edbauer. Rhetoric’s Mechanics: Retooling the Equipment of Writing Production. College Composition and Communication, vol. 60, no. 2, Dec. 2008, pp. 366-387.

Roozen, Kevin. Reflective Interviewing: Methodological Moves for Tracing Tacit Knowledge and Challenging Chronotopic Representations. A Rhetoric of Reflection, 2016, pp. 250-267.

Russell, David R. Rethinking Genre in School and Society: An Activity Theory Analysis. Written Communication, vol. 14, no. 4, 1997, pp. 504-554.

Rutz, Carol. Delivering Composition at a Liberal Arts College: Making the Implicit Explicit. Delivering College Composition: The Fifth Canon, 2007, pp. 60-71.

Salvador, Tony, et al. Design Ethnography. Design Management Journal, vol. 10, no. 4, 1999, pp. 35-41.

Schryer, Catherine F. Investigating Texts in Their Social Contexts: The Promise and Peril of Rhetorical Genre Studies. Writing in Knowledge Societies, edited by Doreen Starke-Meyerring et al., WAC Clearinghouse and Parlor Press, 2011, pp. 31-52.

---. Records as Genre. Written Communication, vol. 10, no. 2, 1993, pp. 200-234.

---. Structure and Agency in Medical Case Presentations. Writing Selves/Writing Societies: Research from Activity Perspectives, edited by Charles Bazerman and David Russell, The WAC Clearinghouse and Mind, Culture, and Activity, 2003, pp. 62-96, https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/selves_societies/schryer/schryer.pdf.

Skains, R. Lyle. The Adaptive Process of Multimodal Composition: How Developing Tacit Knowledge of Digital Tools Affects Creative Writing. Computers and Composition, vol. 43, Mar. 2017, pp. 106-117, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2016.11.009.

Slattery, Shaun. Undistributing Work Through Writing: How Technical Writers Manage Texts in Complex Information Environments. Technical Communication Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 3, 2007, pp. 311-325, https://doi.org/10.1080/10572250701291046.

Software Engineering Institute. Intelligence Writing: Why It Matters. Carnegie Mellon University, 2020, https://fedvte.usalearning.gov/publiccourses/ICI/course/videos/pdf/ICI_D02_S01_T12_STEP.pdf.

Swales, John M. A Working Definition of Genre. Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings, Cambridge UP, 1990, pp. 45-58.

Toulmin, Stephen. Human Understanding. Princeton University, 1972.

Van Ittersum, Derek, and Kory Lawson Ching. Composing Text / Shaping Process: How Digital Environments Mediate Writing Activity. Computers and Composition Online, Fall 2013, https://www2.bgsu.edu/departments/english/cconline/composing_text/webtext/index.html.

Vogel, Kathleen M., and Michael A. Dennis. Tacit Knowledge, Secrecy, and Intelligence Assessments: STS Interventions by Two Participant Observers. Science, Technology, & Human Values, vol. 43, no. 5, 2018, pp. 834-863.

Yancey, Kathleen, et al. Writing across Contexts: Transfer, Composition, and Sites of Writing. Utah State University Press, 2014.

Tech Trajectories from Composition Forum 49 (Summer 2022)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/49/tech-trajectories.php

© Copyright 2022 Gwendolynne Reid, Christopher Kampe, and Kathleen M. Vogel.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 49 table of contents.